Years After the Constitutional Convention of 1787, in the Throes of the Civil War, America’s Leaders Look to the Founders—and the Constitution—to Guide the Nation out of Slavery

It is often said that the Constitution is “a bundle of compromises,” implying that those who wrote the document abandoned principle in favor of cutting eighteenth-century backroom deals whenever possible to protect their own interests.…But the presence of compromise—often simply splitting the difference—does not necessarily prove the principle was thrown by the wayside.…In some cases, accepting compromise might be the wise course in order to preserve principles that might be fully achieved only with the passage of time. Which is to say that any compromise must be understood in light of the larger principles at issue.

—Matthew Spalding1—

Part 2 is available here.

Links to all the articles in this series are available here.

Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is “perhaps the most famous speech ever—and it took two minutes.” Yet many do not know the details about the ceremony at which Lincoln spoke. They are worthy of our consideration today. We begin with background information about the two Civil War battles that led up to that ceremony.

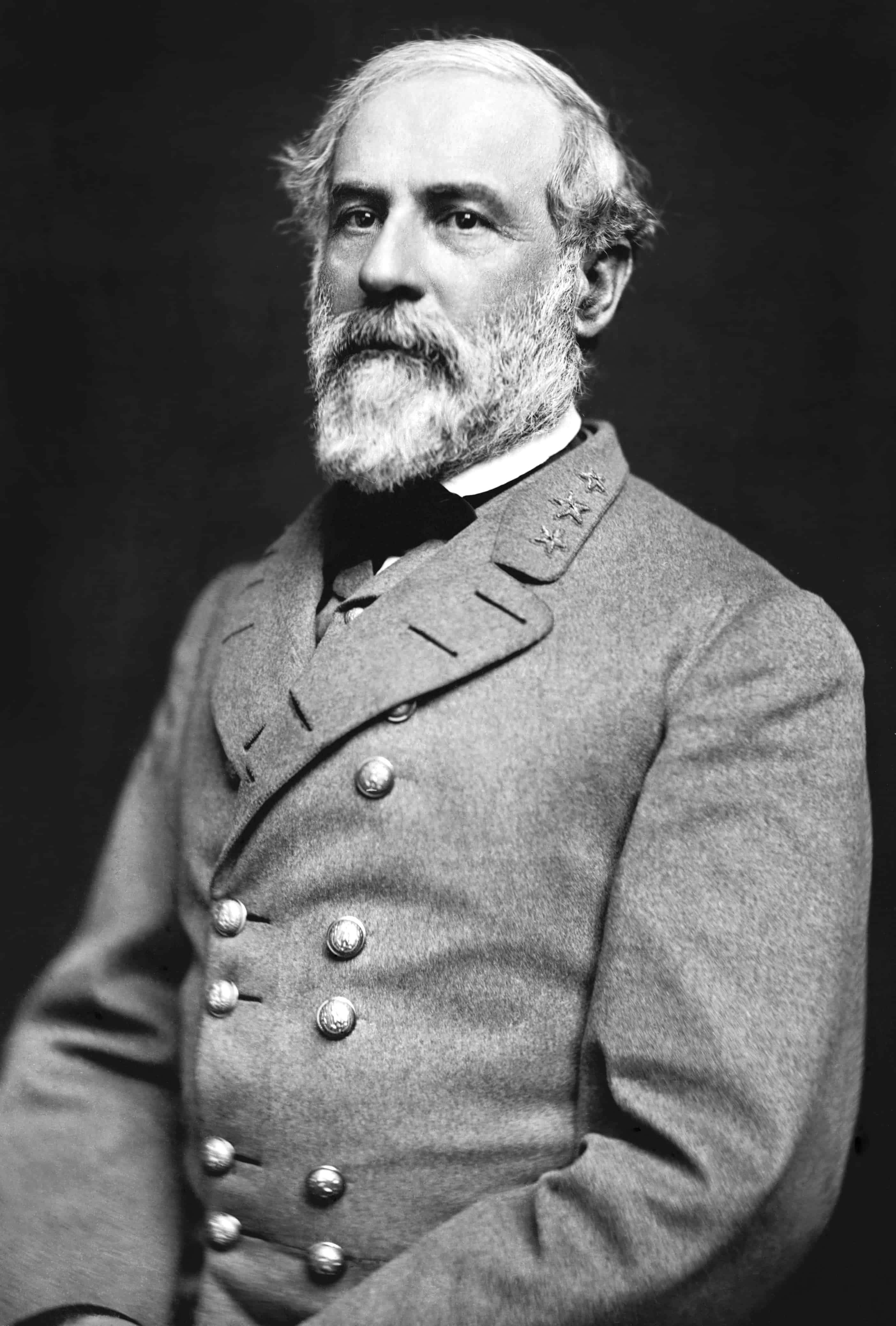

On July 1–3, 1863, Union and Confederate troops engaged in a conflict that resulted in the highest number of casualties of any of the battles of the American Civil War. Fighting occurred in and near the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. General Robert E. Lee led his Army of Northern Virginia against Union troops commanded by Major General George Meade. Lee hoped to capitalize on the success Confederate forces had seen at Chancellorsville, in northern Virginia, on April 30–May 6. That victory had come at the cost of heavy casualties, however.

On July 1–3, 1863, Union and Confederate troops engaged in a conflict that resulted in the highest number of casualties of any of the battles of the American Civil War. Fighting occurred in and near the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. General Robert E. Lee led his Army of Northern Virginia against Union troops commanded by Major General George Meade. Lee hoped to capitalize on the success Confederate forces had seen at Chancellorsville, in northern Virginia, on April 30–May 6. That victory had come at the cost of heavy casualties, however.  On the Confederate side, 10,746 troops were killed or wounded, and on the Union side, 11,368. Significantly for the South, Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was fatally shot on May 2 by friendly fire at Chancellorsville. Jackson died several days later, on May 10. While Lee was encouraged by the victory at Chancellorsville, Jackson’s death was a severe blow. Lee described the loss as being akin to his losing his right arm.

On the Confederate side, 10,746 troops were killed or wounded, and on the Union side, 11,368. Significantly for the South, Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was fatally shot on May 2 by friendly fire at Chancellorsville. Jackson died several days later, on May 10. While Lee was encouraged by the victory at Chancellorsville, Jackson’s death was a severe blow. Lee described the loss as being akin to his losing his right arm.

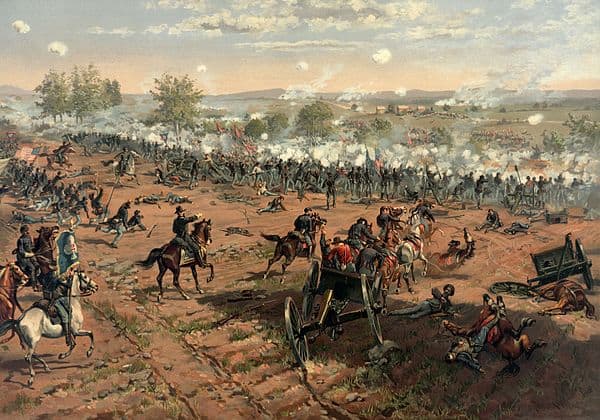

Following the Battle of Chancellorsville, in the latter part of June, General Lee resolved to go on the offensive, and he led army into south-central Pennsylvania. On Wednesday,  July 1, the advancing Confederates clashed with the Union’s Army of the Potomac, commanded by General George G. Meade, at the crossroads town of Gettysburg. The next day saw even heavier fighting, as the Confederates attacked the Federals on both left and right. On July 3, Lee ordered an attack by fewer than 15,000 troops on the enemy’s center at Cemetery Ridge. The assault, known as “Pickett’s Charge,” [pictured at the top] managed to pierce the Union lines but eventually failed, at the cost of thousands of rebel casualties, and Lee was forced to withdraw his battered army toward Virginia on July 4.

July 1, the advancing Confederates clashed with the Union’s Army of the Potomac, commanded by General George G. Meade, at the crossroads town of Gettysburg. The next day saw even heavier fighting, as the Confederates attacked the Federals on both left and right. On July 3, Lee ordered an attack by fewer than 15,000 troops on the enemy’s center at Cemetery Ridge. The assault, known as “Pickett’s Charge,” [pictured at the top] managed to pierce the Union lines but eventually failed, at the cost of thousands of rebel casualties, and Lee was forced to withdraw his battered army toward Virginia on July 4.

The Battle of Gettysburg was a turning point in the American Civil War. Combined casualties—the dead and wounded on both sides—numbered from 46,000 to 51,000.

Dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg

Just over four months after the pivotal battle, in a public ceremony on the afternoon of November 19, 1863, the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg was dedicated. A month earlier, efforts had begun to relocate the bodies of slain soldiers from the battlefield, where they had been buried initially, to the cemetery. David Wills, representing the committee in charge of the ceremony, invited President Lincoln to speak. Wills wrote, “It is the desire, that, after the Oration, you, as Chief Executive of the nation, formally set apart these grounds to their sacred use by a few appropriate remarks.”

“The oration” was to be delivered by featured speaker Edward Everett. Well known, eloquent, and very articulate, Everett had served in numerous public leadership positions, including governor of Massachusetts, Minister to Great Britain, a US Representative, a US Senator, and US Secretary of State. Lengthy speeches were typical at dedication ceremonies during this time period, and Everett’s speech on this occasion was no exception. He crafted and delivered from memory an oration “full of beautiful language and logic, that explained the significance and the tragedy of the Battle of Gettysburg, the standoff during the Civil War with the most causalities, often [now] thought of as a turning point.” Everett talked for two hours. You can read his complete speech here. The featured speaker concluded with these words.

“The oration” was to be delivered by featured speaker Edward Everett. Well known, eloquent, and very articulate, Everett had served in numerous public leadership positions, including governor of Massachusetts, Minister to Great Britain, a US Representative, a US Senator, and US Secretary of State. Lengthy speeches were typical at dedication ceremonies during this time period, and Everett’s speech on this occasion was no exception. He crafted and delivered from memory an oration “full of beautiful language and logic, that explained the significance and the tragedy of the Battle of Gettysburg, the standoff during the Civil War with the most causalities, often [now] thought of as a turning point.” Everett talked for two hours. You can read his complete speech here. The featured speaker concluded with these words.

Surely I would do no injustice to the other noble achievements of the war, which have reflected such honor on both arms of the service, and have entitled the armies and the navy of the United States, their officers and men, to the warmest thanks and the richest rewards which a grateful people can pay. But they, I am sure, will join us in saying, as we bid farewell to the dust of these martyr-heroes, that wheresoever throughout the civilized world the accounts of this great warfare are read, and down to the latest period of recorded time, in the glorious annals of our common country, there will be no brighter page than that which relates The Battles of Gettysburg.

After Everett finished speaking, the Baltimore Glee Club sang a hymn. Then President Lincoln rose and spoke very briefly. Delivering what we now know as his “Gettysburg Address,” the president wasted no time in honing in on the purpose for which the nation had been founded “four score and seven years” earlier: The Founders “brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Lincoln highlighted a similar theme as he concluded his brief remarks, challenging his hearers “that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Lincoln (highlighted in sepia) at Gettysburg. This is one of two confirmed photos of the president on this occasion.

Among those deeply moved by Lincoln’s remarks was Edward Everett himself. The next day, he wrote to the president and said, “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

Echoing the Nation’s Founders

In two minutes and with words that we still remember today, Lincoln reunited in Americans’ minds the war effort and the principles upon on the nation had been founded. He reaffirmed “liberty…and…the proposition that all men [—people—] are created equal.” And although the Founders did not use these words in the founding documents, Lincoln upheld their ideal of government “of the people, by the people, [and] for the people.” Eleven months earlier, commensurate with these principles, the president issued the Emancipation Proclamation which, with “a single stroke,…changed the federal legal status of more than 3 million enslaved people in the designated areas of the South from ‘slave’ to ‘free.’”

Meet Frederick Douglass

President Lincoln wasn’t alone in affirming the founding principles of America as the nation moved to end the scourge of slavery, but perhaps no one became a more articulate defender of the US Constitution than Frederick Douglass.

We present a brief summary of Douglass’s early years here to demonstrate that he knew all about slavery, for he experienced it firsthand. He was no mere observer or bystander. His insights on slavery and racism in relation to the Constitution, therefore, need to be appreciated and heeded in our day. In fact, I believe they need to be rediscovered and showcased for everyone to hear and understand.

Born into Slavery

On a plantation in Talbot County, Maryland, Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in February, 1818—we’re uncertain of the exact day—as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. It was rumored that his father was his master, but he was unable to verify the rumor. Young Frederick never knew his mother, for he was separated from her early on, and she died when Frederick was ten. He lived with his maternal grandmother for several years, then at age seven was separated from her.

Frederick was moved several times in during his childhood and finally was sent to Baltimore to serve Hugh and Sophia Auld in that city. Sophia began to teach 12-year old Frederick the alphabet, but Hugh disapproved and eventually convinced his wife slaves ought not to be educated. Fortunately, it was too late! Frederick now knew the alphabet, and he worked to teach himself to read and write. By observing both children and adults and by practicing reading whenever he could, he was able to master these skills. As he read newspapers, books, brochures, the Bible, and other literature, the young man was able to formulate his own perspectives on slavery and other issues. He later said that The Columbian Orator, a textbook for school children published in 1797, heavily influenced his thinking.

At thirteen, Frederick learned from a white Methodist preacher that God loved him in a personal and life-changing way. Later, Frederick recalled,

He thought that all men, great and small, bond and free, were sinners in the sight of God; that they were by nature rebels against his government; and that they must repent of their sins, and be reconciled to God through Christ.

He also described the change that took place in his own heart.

Though for weeks I was a poor broken-hearted mourner traveling through doubts and fears, I finally found my burden lightened, and my heart relieved. I loved all mankind, slaveholders not excepted, though I abhorred slavery more than ever. I saw the world in a new light and my great concern was to have everybody converted. My desire to learn increased, and especially did I want a thorough acquaintance with the contents of the Bible.

Still a slave, Frederick was sent to work for William Freeland. On Freeland’s plantation, Frederick taught his fellow slaves to read the New Testament at weekly Sunday Bible study. The class grew to more than 40. Mr. Freeland did not resist Frederick’s effort, but plantation owners nearby became uneasy and even angry over the idea of educating slaves. They raided Frederick’s class and put an end to the Bible and reading lessons the young slave was giving.

In 1833 Frederick turned 15. He was placed under the authority and in the service of Edward Covey, a man with a reputation of treating slaves harshly. Soon Frederick turned 16, and Mr. Covey was using his “slave-breaking” approach against Frederick with abandon. He routinely whipped and beat the teenager, who almost gave up in despair. Frederick began to resist physically, though, and Covey stopped beating him after Frederick overpowered him in a fight.

Freedom!

On several occasions, Frederick attempted to escape to freedom. He was unsuccessful until September 3, 1838. In less than a full day, he made his way to New York City and freedom. Later he would describe the feelings he had when he arrived on free soil. His statement, a portion of which we present below, showcases his expert communication skills.

My free life began on the third of September, 1838. On the morning of the fourth of that month, after an anxious and most perilous but safe journey, I found myself in the big city of New York, a FREE MAN—one more added to the mighty throng which, like the confused waves of the troubled sea, surged to and fro between the lofty walls of Broadway. Though dazzled with the wonders which met me on every hand, my thoughts could not be much withdrawn from my strange situation. For the moment, the dreams of my youth and the hopes of my manhood were completely fulfilled. The bonds that had held me to “old master” were broken. No man now had a right to call me his slave or assert mastery over me. I was in the rough and tumble of an outdoor world, to take my chance with the rest of its busy number. I have often been asked how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath and the “quick round of blood,” I lived more in that one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe. In a letter written to a friend soon after reaching New York, I said: “I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.” Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.

In 1837, several months before arriving in New York, Frederick had met a free black woman in Baltimore. Anna Murray captivated his heart. He sent for her after obtaining his freedom, and the two were married just days later, on September 15, 1838. Their marriage would last until her death nearly 44 years later. To avoid being caught, the couple initially used the surname Johnson. Soon they would arrive and settle in New Bedford, Massachusetts and would stay for a while with an abolitionist couple named Nathan and Mary Johnson. It was then they began introducing themselves as Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Douglass.

In 1837, several months before arriving in New York, Frederick had met a free black woman in Baltimore. Anna Murray captivated his heart. He sent for her after obtaining his freedom, and the two were married just days later, on September 15, 1838. Their marriage would last until her death nearly 44 years later. To avoid being caught, the couple initially used the surname Johnson. Soon they would arrive and settle in New Bedford, Massachusetts and would stay for a while with an abolitionist couple named Nathan and Mary Johnson. It was then they began introducing themselves as Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Douglass.

Advocate for Liberty

In 1841, Douglass met William Lloyd Garrison and John A. Collins—two prominent abolitionists—at an anti-slavery convention. Collins suggested Douglass become a paid speaker for the anti-slavery cause, and Douglass agreed to do so for three months. He was so well-received by audiences that the arrangement lasted for four years!

In many speeches, Douglass told of his life as a slave. In 1845 he used those presentations as the starting point for an autobiography of his life. In both America and Europe, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave was wildly popular, but many challenged the idea that a former slave could become such an excellent writer—especially without formal training. According to cliffsnotes.com, “Some thought that the text was a clever counterfeit document produced by abolitionists and passed off as Douglass’s writing. In fact, Douglass was so frequently confronted by such skeptics in the North that he had to finally demonstrate his oratory skills in order to prove his intellectual capacity.”

History.com summarizes Douglass’s life as an advocate for freedom this way:

Frederick Douglass (1818-95) was a prominent American abolitionist, author and orator. Born a slave, Douglass escaped at age 20 and went on to become a world-renowned anti-slavery activist. His three autobiographies are considered important works of the slave narrative tradition as well as classics of American autobiography. Douglass’s work as a reformer ranged from his abolitionist activities in the early 1840s to his attacks on Jim Crow and lynching in the 1890s. For 16 years he edited an influential black newspaper and achieved international fame as an inspiring and persuasive speaker and writer. In thousands of speeches and editorials, he levied a powerful indictment against slavery and racism, provided an indomitable voice of hope for his people, embraced antislavery politics and preached his own brand of American ideals.

Defender of the Constitution

Indeed, Douglass was a powerful force for the cause of freedom and liberty for all. Yet we must understand that his “own brand of American ideals” did not represent a departure from the principles the founders enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution. This point is at the heart of this article.

Douglass’s “own brand of American ideals” did not represent a departure from the principles the founders enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution. In fact, it affirmed them.

It was widely known that abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison believed the Constitution upheld and sanctioned slavery in the United States: “Calling the Constitution a ‘covenant with death’ and ‘an agreement with Hell,’ he refused to participate in American electoral politics because to do so meant supporting ‘the pro-slavery, war sanctioning Constitution of the United States.’ Instead, under the slogan ‘No Union with Slaveholders,’ the Garrisonians repeatedly argued for a dissolution of the Union.”

Initially Douglass agreed with these abolitionists because of the compromises on slavery the Framers of the Constitution had forged when they met in 1787. Eventually, though, he studied the matter for himself and was compelled to break with the Garrisonians. He concluded the Constitution actually was an anti-slavery document. In his 1855 autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass recalled,

[W]hen I escaped from slavery, into contact with a class of abolitionists regarding the constitution as a slaveholding instrument, and finding their views supported by the united and entire history of every department of the government, it is not strange that I assumed the constitution to be just what their interpretation made it. I was bound, not only by their superior knowledge, to take their opinions as the true ones, in respect to the subject, but also because I had no means of showing their unsoundness. But for the responsibility of conducting a public journal, and the necessity imposed upon me of meeting opposite views from abolitionists in this state, I should in all probability have remained as firm in my disunion views as any other disciple of William Lloyd Garrison.

My new circumstances compelled me to re-think the whole subject, and to study, with some care, not only the just and proper rules of legal interpretation, but the origin, design, nature, rights, powers, and duties of civil government, and also the relations which human beings sustain to it. By such a course of thought and reading, I was conducted to the conclusion that the constitution of the United States—inaugurated “to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquillity, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessing of liberty”—could not well have been designed at the same time to maintain and perpetuate a system of rapine and murder, like slavery; especially, as not one word can be found in the constitution to authorize such a belief. Then, again, if the declared purposes of an instrument are to govern the meaning of all its parts and details, as they clearly should, the constitution of our country is our warrant for the abolition of slavery in every state in the American Union.

Historian David Barton recounts Douglass’s quest and affirms his conclusions.

As we have seen, Douglass understood a great deal more than the background behind the Three-Fifths Clause; he understood the Constitution as a whole, and he sought to make his findings known to all Americans. Here are a few more of his insights.

- Now, take the Constitution according to its plain reading, and I defy the presentation of a single pro-slavery clause in it. On the other hand it will be found to contain principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.

- Abolish slavery tomorrow, and not a sentence or syllable of the Constitution need be altered. It was purposely so framed as to give no claim, no sanction to the claim, of property in man. If in its origin slavery had any relation to the government, it was only as the scaffolding to the magnificent structure, to be removed as soon as the building was completed.

- The Constitution of the United States knows no distinction between citizens on account of color. Neither does it know any difference between a citizen of a state and a citizen of the United States.

- Interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the constitution is a Glorious Liberty Document!

- There is no negro problem. The problem is whether the American people have loyalty enough, honor enough, patriotism enough, to live up to their own constitution.

Frederick Douglass’s Legacy

As this last statement from Frederick Douglass attests, Americans have not always lived up to the principles upon which their country was founded or to the US Constitution. Dr. Martin Luther King said as much at the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963 in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech:

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the “unalienable Rights” of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

What If?

While Dr. King was right to point out that white Americans had failed to treat blacks as their equals, he also was right in echoing Frederick Douglass’s confidence in the Founders of America and in the Constitution they drafted. The principles on which this country was founded and the US Constitution continue to pull us back to our obligation to fulfill the promise to let every individual, regardless of race, live as a free individual in an ordered society. It’s true that a great Civil War should not have had to occur to end slavery; and it’s equally true that blacks should not have had to endure the struggles they faced during the Civil Rights era just to be treated fairly. Yet it is not true that slaves automatically would have been better off if the anti-slavery delegates at the Constitutional Convention had drawn a line in the sand and refused to budge on the issue of slavery. Progressives are wont to imply anti-slavery delegates at the convention ought to be blamed for allowing slavery to continue because they did not give the pro-slavery delegates an ultimatum. Walter Williams writes,

A question that we might ask those academic hustlers who use slavery to attack and criticize the legitimacy of our founding is: Would black Americans, yesteryear and today, have been better off if the Constitution had not been ratified—with the Northern states having gone their way and the Southern states having gone theirs—and, as a consequence, no union had been created? I think not.

It is clear that like Mr. Williams, Frederick Douglass keenly understood that preservation of the Union under the provisions of the Constitution eventually would make slaves infinitely better off. With freedom they were afforded equality and rights, at least as far as the founding documents were concerned. And there was no better place to start than with the founding principles enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—the supreme law of the land.

Preservation of the Union under the provisions of the Constitution eventually would make slaves infinitely better off.

This video not only provides a review of our excursion into history in this series thus far; it also helps us understand the harsh realities the Framers knew they would face if the colonies, now independent states, did not remain united.2

I conclude with these additional insights from Walter Williams.

Ignorance of our history, coupled with an inability to think critically, has provided considerable ammunition for those who want to divide us in pursuit of their agenda. Their agenda is to undermine the legitimacy of our Constitution in order to gain greater control over our lives. Their main targets are the nation’s youths. The teaching establishment, at our public schools and colleges, is being used to undermine American values.

To counter this misinformation, we must teach our children and their peers the truth about leaders who understood both the value and the price of authentic liberty.

Men like Frederick Douglass.

Copyright © 2016 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All Rights Reserved.

Part 4 is available here.

Notes:

1Matthew Spalding, We Still Hold These Truths: Rediscovering Our Principles, Reclaiming Our Future, (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2009), 130.

2I noticed one error in this presentation. At 6 minutes, 50 seconds in, the host of the program, Dan Willoughby, states, “Two provisions were put into the Constitution that might lend a hand to the abolitionists’ cause. First was a clause that would not allow slave importation into the states after a period of 20 years, and the other tied federal taxation to population in the same way representation was linked.” The underlined portion is not entirely correct. While the Slave Trade Clause prohibited Congress from ending the slave trade until 1808 (and permitted it to do so as of January 1 of that year), the clause itself did not end it, nor did it require Congress to end it. On March 2, 1807, Congress passed, and president Jefferson signed into law, a provision to end the trade effective January 1, 1808.

Links to websites are provided for information purposes only. No citation should be construed as an endorsement.

Be First to Comment