This material also corresponds to footnote #21 in the PDF and printed booklet editions of “Ditching Socialism in the New World,” and to footnote #21 in Heed the Pilgrims.

In his account of the Pilgrims’ journey to the New World and their settlement at what would become known as Plymouth, Massachusetts, William Bradford (1590-1657) writes,

So they began to consider how to raise more corn, and obtain a better crop than they had done, so that they might not continue to endure the misery of want. At length after much debate, the Governor, with the advice of the chief among them, allowed each man to plant corn for his own household, and to trust to themselves for that; in all other things to go on in the general way as before. So every family was assigned a parcel of land, according to the proportion of their number with that in view, — for present purposes only, and making no division for inheritance, — all boys and children being included under some family. This was very successful. It made all hands very industrious, so that much more corn was planted than otherwise would have been by any means the Governor or any other could devise, and saved him a great deal of trouble, and gave far better satisfaction. The women now went willingly into the field, and took their little ones with them to plant corn, while before they would allege weakness and inability; and to have compelled them would have been thought great tyranny and oppression.

Bradford, William. Of Plymouth Plantation (p. 116). Portcullis Books. Kindle Edition. Edited by Harold Paget. Book II, Chapter IV

Paraphrase/Summary as presented in “Ditching Socialism in the New World”:

We knew we couldn’t continue on as we had. Had we done so, all of us would have starved to death. We discussed it thoroughly among ourselves, considering all our options. In the end, we decided that I as governor, taking into account the advice given by the other leaders among us, would assign a tract of land to each family. Each one, in turn, would be responsible to plant corn and other crops for themselves.

In other words, we ditched the communal system. Our investors simply would have to live with that! What kind of return on their investments would they receive if all of us had starved? We traded the failed system for one that emphasized

-

-

-

-

- the benefits of private property and

- the responsibilities of the owner(s) it to effectively manage the resources in his/their charge.

-

-

-

As we assigned the land, we were mindful that larger families would need more resources, so we made our decisions accordingly. We weren’t thinking about inheritance or other future matters, but mainly about immediate needs. Children who had been orphaned and other single individuals were assigned to families—and so management of work responsibilities would belong strictly to each family unit. Also—and this is key—so would the corps they produced. In this way, laziness naturally would be penalized, and hard work rewarded.

The change was remarkable and immediate! Whereas before the men in our company had looked for excuses not to work and had complained when they did, they now labored willingly and eagerly. More corn was planted than would have been under any other system I or anyone else could have devised. It wasn’t just the men, either! Wives and children also worked in the fields, and they apparently wanted to! Before we adopted this system, urging a woman to till the ground and plant corn was thought to be oppressive and mean.

This material relates to footnote #8 in the article “Ditching Socialism in the New World.” It relates as well to footnote #21 in the PDF and printed booklet editions.

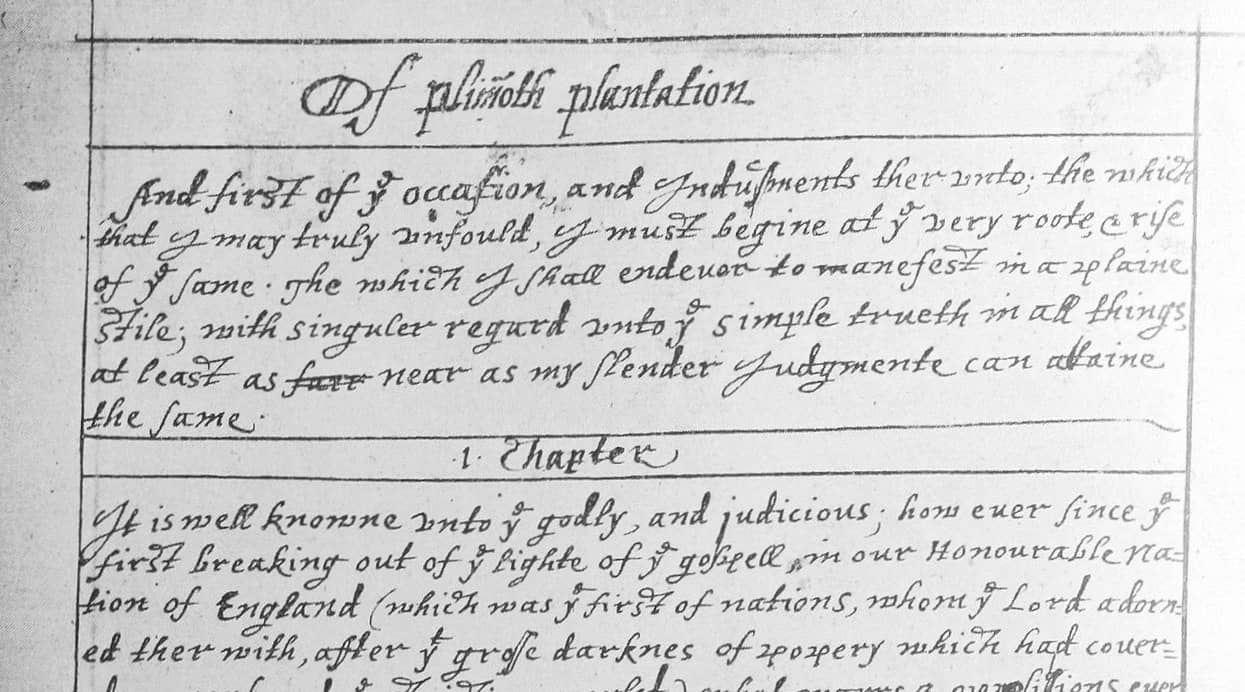

top image: Front page of William Bradford’s manuscript for Of Plymouth Plantation

Paraphrase copyright © 2019 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All rights reserved.