This material also corresponds to footnote #24 in the PDF and printed booklet editions of “Ditching Socialism in the New World,” and to footnote #24 in Heed the Pilgrims.

In his account of the Pilgrims’ journey to the New World and their settlement at what would become known as Plymouth, Massachusetts, William Bradford (1590-1657) writes,

Now the original settlers were afraid that their corn, when it was ripe, would have to be shared with the new-comers, and that the provisions which the latter had brought with them would give out before the year was over, — as indeed they did. So they went to the Governor and begged him that as it had been agreed that they should sow their corn for their own use, and accordingly they had taken extraordinary pains about it, they might be left to enjoy it. They would rather do that than have a bit of the food just come in the ship. They would wait till harvest for their own and let the new-comers enjoy what they had brought; they would have none of it, except what they could purchase by bargain or exchange. Their request was granted them and it satisfied both sides; for the new-comers were much afraid the hungry settlers would eat up the provisions they had brought, and then that they would fall into like conditions of want.

Bradford, William. Of Plymouth Plantation (p. 124). Portcullis Books. Kindle Edition. Book II, chapter IV

Paraphrase/Summary as presented in “Ditching Socialism in the New World”:

There’s more. Thanks for your patience as I explain even further. Be assured, though, I’m almost done. In November of 1621, the ship Fortune arrived with about 35 new colonists. The ship brought us mouths to feed, but no supplies; and our rations were cut in half. It wasn’t that we wished hardship on anybody, but the additional needs among us made our task even more challenging.

So it’s easy to see how the arrival of new colonists made us wary. We limped along as best we could until we established private property rights and a free-market system in 1623. Soon after we had changed our approach—around July and August of that same year—100 new colonists arrived on two ships, the Anne and Little James. We wanted them to feel welcome, but it quickly became apparent we needed to clarify some matters with them so no unnecessary misunderstanding would occur.

The colonists who had been around from the beginning worried that when the corn they’d planted ripened, the new members of the colony would expect they would be entitled to some. With so many mouths to feed, there wouldn’t be enough corn to go around.

As I indicated, we’d already adopted the new system, and those who had worked hard to plant their own corn had done so with the understanding that what they harvested would be theirs to enjoy. They preferred to eat the crops they had planted as opposed to being fed from any of the food supplies the ships delivered.

So we reached an agreement. The new arrivals would use the food that had come over with them, and the early members of the colony wouldn’t have access to it, except that for which they bargained, or the food they purchased.

This put everyone’s mind at ease. You see, it wasn’t just the “old-timers” who were worried! The new arrivals actually had been afraid their food would be devoured by the settlers who had been around for a while. Isn’t it interesting how all of us tend to view others—even friends and potential friends—with a mutual kind of skepticism?

This material relates to footnote #9 in the article “Ditching Socialism in the New World.” It relates as well to footnote #24 in the PDF and printed booklet editions.

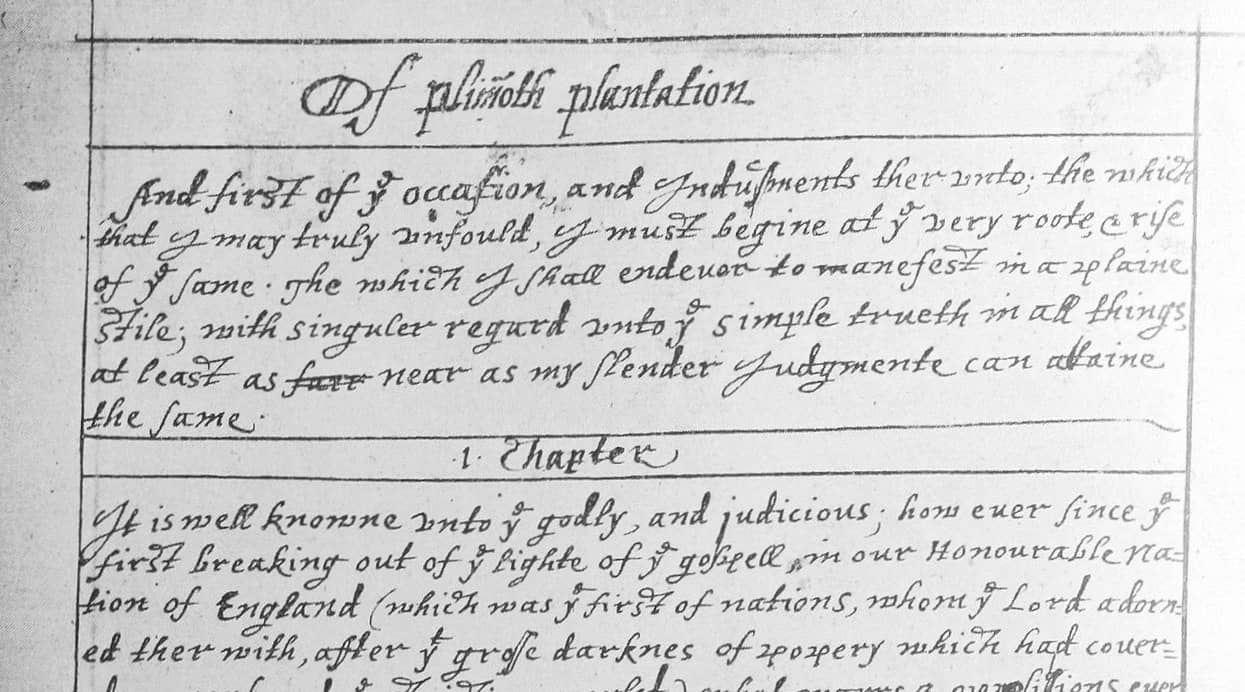

top image: Front page of William Bradford’s manuscript for Of Plymouth Plantation

Paraphrase copyright © 2019 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All rights reserved.