Defog Your Rearview Mirror

Understanding the Historical Context Is Essential to Understanding the Historical Event, and Understanding the Event Is Essential to Rightly Interpreting the Present and Navigating the Future

One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken. Once you give a charlatan power over you, you almost never get it back.

―Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark―

“That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons that history has to teach.”

― Aldous Huxley Collected Essays―

“The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.”

―George Orwell―

Links to all the articles in this series are available here.

On Monday, May 14, 1804, a group of more than thirty volunteers who became known as the Corps of Discovery departed in three boats from Camp Dubois in Indiana Territory for St. Charles, Missouri. There they would join Captain Meriwether Lewis, the leader of the expedition of which they had agreed to be a part. Second-in-command was Second Lieutenant William Clark.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

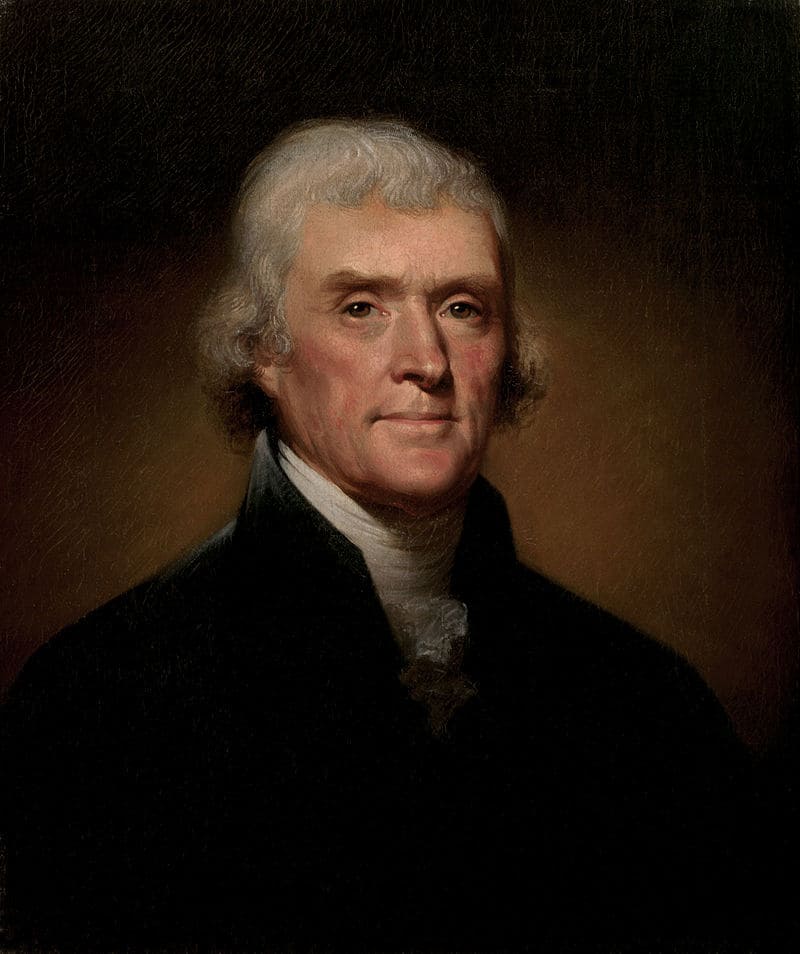

On May 21, the group headed west by following the Missouri River. Their mission was to explore the vast area of land the United States had acquired through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. This investment is considered one of President Thomas Jefferson’s greatest accomplishments.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition ended 28 months after it began—on September 23, 1806, when the men returned to St. Louis. From that city, Lewis, Clark, and their companions had journeyed up the Missouri River, “across the Rocky Mountains, and down the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean.” When travel on the water was too dangerous, the explorers carried their boats on land. Sacajawea, a Native American woman they met on their journey, helped them by serving as a guide. During the expedition, the explorers and observers recorded their findings. They kept journals, drew maps, and collected samples of various plants, all of which helped to make the effort a resounding success. Having walked, hiked, ridden horses, and rowed boats, the pioneers traveled about 8,000 miles. The painting at the top was painted by by Charles Marion Russell (1864-1926) and is titled Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition is all the more fascinating because it really happened. Yet suppose I told you that after they’d collected several unusual plant samples, Lewis and Clark sent them back to President Jefferson by Federal Express. Ridiculous? Absolutely! Even so, such an idea is no less ridiculous than some modern interpretations of past events that fail to consider the contexts of those events—the social and cultural climates of the times. It’s too bad the ridiculous nature of many modern interpretations usually is subtle, almost to the point of being undetectable. Were it more blatant, fewer people would be duped.

Many modern interpretations of historical events are just as ridiculous as the suggestion that Lewis and Clark were able, on their expedition, to send plant samples back to President Jefferson by Federal Express.

Quite often, as sloppy historians interpret the past through the lens of modern perspectives on everything from medicine to the economy to social status, they also make a multitude of unwarranted and often condescending judgments. H. L. Mencken, a writer known for his own brand of sensationalism, once said that a historian is “an unsuccessful novelist.” Unfortunately, he was all too accurate. Note as well the quotes showcased at the top of this article. As much as I disagree with Carl Sagan on a host of issues, he was absolutely right about being bamboozled. We need to realize people are bamboozled by sloppy and agenda-driven historians as well as politicians.

When studying history, follow these important guidelines: Learn all you can, not just about what happened, but also about what led up to it. Seek to understand the thinking of the times. Do not blame the people of a past era for not knowing pertinent information we know today, especially information they had no way to learn. Remember that we have hindsight, and they did not. Some even possessed a lot more foresight than we tend to believe. Look beyond surface meanings and consider implications and repercussions. Consider the worldview perspectives of historical subjects. Don’t just observe what people did, but also what they didn’t do. If we will seek to do these things, the lessons we derive from history’s vaults will be far more accurate than they otherwise would.

When studying history, learn all you can, not just about what happened, but also about what led up to it. Seek to understand the thinking of the times. Do not blame the people of a past era for not knowing pertinent information we know today, especially information they had no way to learn. Remember that we have hindsight, and they did not. Some even possessed a lot more foresight than we tend to believe. Look beyond surface meanings and consider implications and repercussions. Consider the worldview perspectives of historical subjects. Don’t just observe what people did, but also what they didn’t do.

In this post and the next (and possibly other posts as well) I want to consider the issue of slavery in the United States—specifically the approach the architects of the US Constitution took in dealing with this divisive and sensitive issue. I do this in part because of the recent escalation of racial tensions and incidents of violence in our country. Did our Founders intend to perpetuate slavery based on race, or did they in fact set the stage for it eventually to be eradicated? Is the Constitution a racist document, or does it reflect the Declaration’s core principles that “all men [persons, human beings] are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”?

Obviously, slavery continued in America for many years after the Constitution took effect, but this fact alone may not tell the entire story. A great deal is at stake here. The belief that the Framers of the Constitution wanted slavery to continue forever understandably will make it harder for blacks to trust governmental authorities, including police. Yet, if we dig deeper and come to understand many of the relevant historical details, we just might discover truths that can help ease some of today’s racial tensions and conflicts.

We alluded to the issues of slavery and its relationship to the Constitution in a previous post but did not have opportunity to explore it in any significant detail. Perhaps no provision in the Constitution as it was originally drafted is more misunderstood than the “Three-Fifths Clause,” which resulted from the “Three-Fifths Compromise.” While it is technically correct to say the Constitution originally authorized counting each slave as three-fifths of a person, this leaves the erroneous impression that the delegates to the Constitutional Convention and the Founders of America believed that a slave was less than a human being.

I first want to debunk the myth that the Constitution’s Three-Fifths Cause, in and of itself, is clear evidence that the Constitution’s Framers considered a black man or woman as less than a person. Then we’ll examine the Three-Fifths Clause in some detail, as well as the context in which it was adopted. I believe you’ll find our historical discoveries extremely enlightening. They will bolster your faith in the founding of our country, and in the Constitution as well.

Here’s a portion of what we said earlier about the dawn of the US government under the Constitution (not all original citations have been included here).

After the American Revolution, the thirteen states rejoiced over their independence, but they still were thirteen individual states, each of which, in many ways, acted as an individual country. Previously the war against Great Britain had united these Virginians, New Yorkers, Pennsylvanians, Marylanders, and the residents of the other states, but now other matters confronted the new nation. How could the states work together? Could they establish a central government that would acknowledge states’ sovereignty, yet unify the states to address the issues that would confront them all?

An attempt was made in the Articles of Confederation. This document was drafted under the authority of the Second Continental Congress, which appointed a committee to begin the work on July 12, 1776. In the latter part of 1777, a document was sent to the states for ratification. All the states had approved it in the early part of 1781. The states now had a new central government, but it wasn’t long before problems arose. The national government was too weak. It had no executive authority and no judiciary. Too high a hurdle had been established for the passage of laws. Furthermore, the states had their own monetary systems, so understandably, buying and selling across state lines became difficult. Without free trade between the states, the national economy was severely hindered.…

Accordingly, the states were asked to send their representatives to Philadelphia in May of 1787. This meeting become the Constitutional Convention. Delegates soon realized they shouldn’t try to fix the Articles of Confederation but needed to replace it altogether. The Convention met from May 25 to September 17, 1787.

According to Article VII of the proposed Constitution, the document would become binding on all thirteen states after it had been ratified by nine. New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify on Saturday, June 21, 1788. The remaining states followed, but after New Hampshire’s decisive vote it was “agreed that government under the U.S. Constitution would begin on March 4, 1789.” Thus, the last two states to ratify, North Carolina and Rhode Island, did so after the Constitution already had taken effect. On November 21, 1789, North Carolina officially embraced the Constitution, and on May 29, 1790, by just two votes, Rhode Island joined the rest of the original colonies, making it unanimous.

Signing of the Constitution by Thomas P. Rossiter (1818-1871)

When the Constitution was being drafted in 1787, however, ratification of the thirteenth of thirteen states was three years and a great many debates away. As they hammered out the details, delegates crafted a Constitution that differed from the Articles of Confederation in a large number of ways. One of these related to the legislative body. Some delegates, principally those from small states, felt each state should have an equal share of lawmakers. Others, mainly those from the larger states, believed that representation in the legislative body should reflect each state’s population. The Articles of Confederation had set up just one legislative body, but the new Constitution established two—the Senate and the House of Representatives. This arrangement affirmed both perspectives. In the Senate, each state, regardless of size, would have two Senators. In the House, the number of representatives from each state would be determined by that state’s population. Thus, in the House, the larger states would have more representatives than the smaller ones. For a bill to become law, it would have to pass both houses of Congress. This truly was was a brilliant approach.

Having agreed to this model, the delegates then had to adopt a formula for determining the number of representatives each state would have in the House. Delegates resolved that each state would get one Representative for every 30,000 people. Even though only men could vote, women and children were counted along with them. But how should slaves be counted? Gary DeMar writes, “The Northern states did not want to count slaves. The Southern states hoped to include slaves in the population statistics in order to acquire additional representation in Congress to advance their political [pro-slavery] position.” In the end, it was agreed that in slave states, a Representative would be added for every 50,000 slaves rather than 30,000. In mathematical terms, this effectively meant that that every five slaves would count as three persons for representation purposes, so each individual slave would be counted as three-fifths of a person. This same count also was used to determine amounts states would pay in taxes as well.

As insensitive and as cruel as this may sound in our day, this was not at all about the worth of a slave as a person. Had the Southern states gotten what they wanted, every slave would have been counted as one individual. This would have resulted in a stronger pro-slavery contingent in the House. Had the Northern states gotten their way, no slaves would have been counted at all, and the anti-slavery position in the House of Representatives would have been strengthened to the greatest degree possible. Neither side prevailed. A compromise was reached.

The Three-Fifths Clause read,

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

ARTICLE I, SECTION 2, CLAUSE 3

So, contrary to first impressions, the pro-slavery position was to count slaves as full individuals, and the abolitionist position was to not count them at all! Again, the decision to number slaves in the manner described in the Three-Fifths Clause had absolutely nothing to do with the worth of a slave as a person, but with taxation and with representation of slave states in the House of Representatives.

The pro-slavery position was to count slaves as full individuals, and the abolitionist position was to not count them at all! The Three-Fifths Clause had absolutely nothing to do with the worth of a slave as a person, but with taxation and with representation of slave states in the House of Representatives.

Overcoming the impression one gets when he or she hears that the Constitution authorized counting each slave as three-fifths of a person is difficult enough, but even many of the sources that acknowledge the Three-Fifths Clause was about counting slaves for representative and taxation purposes don’t explain what this actually meant in practical terms (as we have here). Moreover, the sources often go on to condemn, either directly or by implication, the Founders for refusing to draw a line in the sand to end slavery altogether. Consider this description of the Three-Fifths Compromise in “The Making of America: Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of a Nation.”

The Southern states insisted that their slave populations would be counted when assigning seats in the House of Representatives, even though no one seriously considered giving the right to vote to anyone other than white men. This resulted in the “Three-Fifths Compromise,” in which 60% of a state’s slave population would be added to its free population when assigning seats in the House. Sadly, the new nation’s founding document sanctioned slavery: at the insistence of Southern states, the Constitution specifically prohibited Congress from passing any laws that abolished or restricted the slave trade until 1808.1

This makes it sound as if the Southern states got everything they wanted, but, in fact (as we already have said), they did not. Next week, we’ll learn even more about slavery and the Constitution at the founding of America. Among other things, we’ll consider why the anti-slavery delegates at the Constitutional Convention didn’t give their pro-slavery counterparts an ultimatum.

I venture to say that anyone who gives our discussion a fair hearing will find it enlightening and eye-opening. Stay tuned.

Part 2 is available here.

Copyright © 2016 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All Rights Reserved.

top image credit: Corps of Discovery meet Chinooks on the Lower Columbia, October 1805 (Charles Marion Russel, c. 1905)

Note:

1The editors of Time, The Making of America, (New York: Time, Inc., 2005), 83.

Websites in this article have been cited for information purposes only. No citation should be construed as an endorsement.

Be First to Comment