The moderation and virtue of a single character probably prevented this [American] Revolution from being closed, as most other have been, by a subversion of that liberty it was intended to establish.

—Thomas Jefferson, speaking of the character George Washington exhibited during his Newburgh Address and the effect it had on his audience1—

In October of 1781 at Yorktown, Virginia, British troops surrendered to the American Continental Army led by George Washington. The American forces had been aided by Marquis de Lafayette and other French military leaders and troops. The Siege of Yorktown, which lasted from September 28 to October 19, was the last major battle of the American Revolutionary War taking place on land. The battle and the surrender of British forces led to negotiations for an official end to the war, the specifics of which were laid out in the Treaty of Paris of 1783. The document was signed and became official on September 3 of that year.

The war had been won, but in early 1783, the new nation faced a crisis that almost led to its undoing. Troops had returned home but had not been paid, and they and their families desperately needed money to make ends meet. Some had served in the army for years, and understandably, they were angry that Congress had failed to compensate them for their service — whether with money, food, or material goods. Officers met at Newburgh, New York, and they began circulating an anonymous letter denouncing lawmakers for their failure to keep their promises. By the middle of March, open rebellion against the government and the new nation itself was a real possibility.

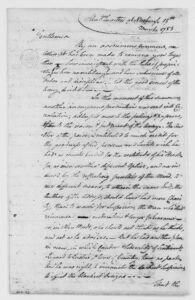

After hearing about the growing ire of the officers and their men, General Washington resolved to urge them to exercise patience. After all, these were his men too. Together they had fought diligently to secure their nation’s independence on the world stage. On March 14, Washington penned a speech he hoped would help avert disaster. We refer to it today as the Newburgh Address.

The next day was a Saturday. When General Washington arrived at the meeting hall where the military men had gathered, all eyes were on him. These men had grown to love their military commander with whom they had endured so much, but they also felt betrayed and cheated. Many were ready to push back against pleas for understanding, even if they came from General Washington himself.

Even so, they were willing to let the General have his say. Washington implored them to think carefully about their new country and its vulnerabilities, for it still was in its infancy. He told the men he would go to bat for them, doing everything he could to see that they would indeed be compensated for their military service. He implored them to be understanding, declaring, in part,

I cannot, in justice to my own belief, & what I have great reason to conceive is the intention of Congress, conclude this Address, without giving it as my decided opinion; that that Honble Body, entertain exalted sentiments of the Services of the Army; and, from a full conviction of its Merits & sufferings, will do it compleat Justice: That their endeavors, to discover & establish funds for this purpose, have been unwearied, and will not cease, till they have succeeded, I have not a doubt. But, like all other large Bodies, where there is a variety of different Interests to reconcile, their deliberations are slow. Why then should we distrust them? and, in consequence of that distrust, adopt measures, which may cast a shade over that glory which, has been so justly acquired; and tarnish the reputation of an Army which is celebrated thro’ all Europe, for its fortitude and Patriotism? and for what is this done? to bring the object we seek for nearer? No! most certainly, in my opinion, it will cast it at a greater distance.

Washington understood that the very cause for which these men had fought so hard during the Revolution was at risk because liberty cannot endure if chaos prevailed. His words were noble and his pleas sincere, but the men ultimately were persuaded, not as much by Washington’s words alone, as by an almost obscure gesture and a comment the General made to explain what he’d done.

Washington understood that the very cause for which these men had fought so hard during the Revolution was at risk because liberty cannot endure if chaos prevailed. His words were noble and his pleas sincere, but the men ultimately were persuaded, not as much by Washington’s words alone, as by an almost obscure gesture and a comment the General made to explain what he’d done.

Washington brought forth a letter a congressman had written to explain the challenges the new government was working hard to address and overcome. He began to read it but soon paused. He reached in his pocket and pulled out…a pair of glasses. The men had never seen the General wear them before. Putting them on, Washington explained, “Please forgive me, gentlemen. I have grown gray during my years of serving my country, and now I also find I am growing blind.”

Please forgive me, gentlemen. I have grown gray during my years of serving my country, and now I also find I am growing blind.

—George Washington—

Washington’s gesture and explanation hit the men in the very core of their beings. They were moved to tears. Yes, they had sacrificed much, but the General’s sterling example reminded them that they were not alone — with regard to either sacrifices made or benefits secured, if they would be willing to see the “big picture.” According to an article at history.com, “Within minutes, the officers voted unanimously to express confidence in Congress and their country.”

“The big picture” was indeed beyond significant. It was captured in words a mere four years later in the Preamble to the US Constitution, which spoke of securing “the Blessing of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.”

Today, on the 241st anniversary of the Newburgh Address, we can be thankful for men like George Washington — men who led their country with integrity, resolve, humility, and grace.

We need men and women like that today — now more than ever!

Will you be one?

Notes:

1William J. Bennett and John T. E. Cribb, The American Patriot’s Almanac: Daily Readings on America (Thomas Nelson: Nashville, 2010), 85. This is the source, not only for Jefferson’s quote, but also for numerous details summarized in this article.

top image credit: The 1781 siege of Yorktown ended with the surrender of a second British army, marking effective British defeat. artist: John Trumbull

Copyright © 2024 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All rights reserved.

Be First to Comment