Currier and Ives print: The First Colored Senator and Representatives, December 31, 1871

Meet the first black members of the United States Congress.

- US Senator Hiram Revels (1827-1901) from Mississippi was the first African-American to serve in the United States Congress. He served in the 41st Congress, which lasted from 1869-1871. Also a preacher, Revels was a powerful speaker. He was a lifelong freedman. Even though he “viewed himself as ‘a representative of the State, irrespective of color,’ he also represented freedmen and, as such, received petitions from black men and women from all states.” Yet he also “favored universal amnesty for former Confederates, requiring only their sworn loyalty to the Union.”

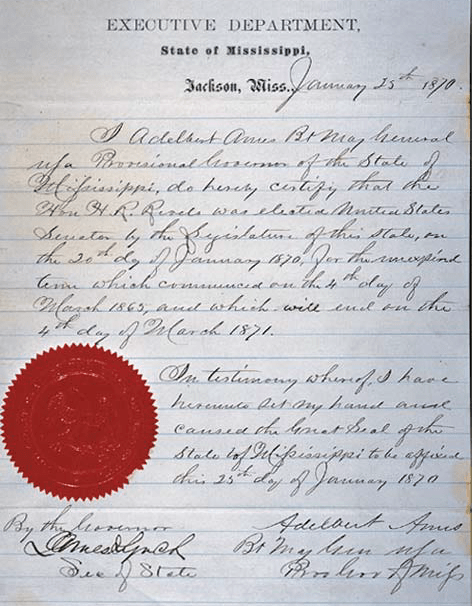

Letter from the Governor and Secretary of State of Mississippi certifying Hiram Rhodes Revels to the US Senate, January 25, 1870

- Benjamin Sterling Turner (1825-1894), a slave, became a successful businessman, then became the first black man to serve in the US House of Representatives from the state of Alabama. He served in the 42nd Congress (1871-1873). Turner’s work in the House of Representatives included efforts to restore the rights of former Confederates. He also sought repeal of a tax on cotton, arguing that it was an especially heavy burden on black Americans. After serving in Congress Turner pulled away from political activity for a time, but in 1880 he participated in the Alabama Labor Union Convention and was a delegate to his party’s political convention in Chicago. He returned to his work in business afterward, but a tough economy ended those efforts. Turner then tried farming but died a poor man on March 21, 1894.

- Robert C. De Large (1842-1874) served in the 42nd Congress as a representative from South Carolina. DeLarge’s parents may have been free and members of different races (or of mixed races themselves), but some records indicate he was born a slave. Either way, remarkably, he completed a high school education at Charleston’s Wood High School. Before entering politics he became a tailor, as well as a farmer. He worked in politics at the state level and then was elected to Congress in 1870. De Large “took his seat on March 4, 1871. Placed on the Committee on Manufactures, he also urged legislation to protect Republicans from intimidation and to protect African Americans from racial violence. Unfortunately, [Christopher C.] Bowen [—the opponent he’d narrowly defeated—] weakened DeLarge’s effectiveness by contesting the election and thereby consuming much of the young congressman’s time. The House Committee on Elections began considering C. C. Bowen v. R. C. DeLarge in December 1871 but failed to reach a conclusion until January 1873. At that time they removed DeLarge from office because such irregularities existed in the election as to make the victor impossible to determine. DeLarge did not pursue reelection because his health had already begun to fail.” He died at 31 years of age.

- Josiah Thomas Walls (1842-1905) was born in Virginia as a slave in 1842. He served as a Confederate soldier because he was required to do so, but in 1862 Union troops captured him in Yorktown. He then volunteered to serve on the side of the Union! He became First Sergeant in the US Colored Troops Infantry Regiment. Serving in Union-occupied Florida, he met and married Helen Ferguson from Florida before leaving the Army in 1865. Walls was elected to the Florida Senate for sessions held in 1869, 1870, 1877, and 1879. In 1871, he became the first African American to represent a Florida congressional district in the US house of Representatives. His opponent contested the election, and nearly two years later, Walls was unseated. Still, his “congressional career was not over. In November 1872, he had won one of the two Florida At–Large seats in the 43rd Congress (1873–1875).” Walls narrowly won again in 1874, but his opponent, Jesse J. Finley, contested that election. Walls’ party was now out of power, and the committee in charge of the decision seated Finley. Walls had been involved in the 42nd, 43rd, and 44th Congresses.

- Jefferson Franklin Long (1836-1907), a Georgian, filled a vacancy in the US House of Representatives during the 41st Congress. The remainder of the term he filled lasted only three months—from January 16, 1871 to March 3, 1871. The first African-American to be elected to the US House of Representatives from his state and the second to be elected to the US House, Long gave just one speech to Congress. That speech also was a first—the first to be delivered by an African-American in the US House. Long gave it on February 1, 1871. He “opposed a measure which would remove voting restrictions on ex-Confederate political leaders because he felt these men still posed a threat to African Americans political freedom if allowed to regain power.” He declared, “If this House removed the disabilities of disloyal men, I venture to prophesy you will again have trouble from the very same men who gave you trouble before.” Long’s efforts to oppose Confederate amnesty failed, and two weeks later, President Grant allowed the legislation to become law without his signature. In less than a month, Long’s term had expired. The former congressman returned to Georgia and campaigned for candidates in his party. Encouraged by Long, a group of freedmen went to the polls together to vote on election day in 1872. Armed white thugs incited a riot to prevent them from voting. Violence erupted and four from Long’s group were killed. Discouraged, Long pulled away from political involvement and focused on business endeavors thereafter. He died in early February, 1907.

- Joseph Hayne Rainey (1832-1887), was from South Carolina. He was the first black American to be elected to the United States House of Representatives. Born a slave, he acquired his freedom when his father purchased it for him and the rest of the family in the 1840s. In 1861, Rainey was conscripted into the Confederate armed services. He served on a ship and was able to escape to Bermuda in 1862. He returned to South Carolina soon after the war. Rainey was part of several Congresses—the 41st, 42, 43rd, 44th, and 45th. He died on August 1, 1877.

“We [Black Americans] are earnest in our support of the Government. We are earnest in the house of the nation’s perils and dangers; and now, in our country’s comparative peace and tranquility, we are earnest for our rights.”

—Representative Joseph Hayne Rainey—

- Robert Brown Elliott (1842-1884) represented constituents in his district in South Carolina during the 42nd and 43rd Congresses. We don’t know much about Elliott’s early years. He may have been born in England to a couple from the West Indies. At 25 years of age, came to South Carolina and began practicing law. He served in the South Carolina House of Representatives after being elected in 1868. South Carolina Governor Robert Scott appointed Elliott as the state’s assistant adjutant general. In this capacity, Elliott was authorized to lead militia across the state to defend blacks from attacks by the Ku Klux Klan. In 1870, he won the congressional seat for the district that included South Carolina’s capital, Columbia. He was well-educated, eloquent, and had a natural confidence that he used to his advantage. Some were apprehensive and wary, as he was willing to push for stronger civil rights legislation for blacks than were other African-American congressmen. Also, being very dark skinned, he was called Congress’ first “genuine African.” History.house.gov, the history website of the House of Representatives, says of Elliott, “Rising racial violence in his home state stirred Elliott to speak. Just before Christmas 1870, a white whiskey peddler allegedly was killed by a group of drunk, black militiamen in the town of Union Courthouse, South Carolina. Thirteen men were arrested in connection with the crime, but before they were tried, the Ku Klux Klan raided several jails, executing the suspects. The Klansmen subsequently posted a notice on the Union Courthouse jail door justifying the lynchings and warning other African Americans in the state.” Later, Elliott delivered a speech in which “he read the letter posted by the Klansmen at the Union Courthouse jail, following it with words about the prejudice against his race: ‘It is custom, sir, of Democratic [newspapers] to stigmatize the negroes of the South as being in a semi–barbarous condition; but pray tell me, who is the barbarian here, the murderer or the victim? I fling back in the teeth of those who make it this most false and foul aspersion upon the negro of the southern States.’”

It is custom, sir, of Democratic [newspapers] to stigmatize the negroes of the South as being in a semi–barbarous condition; but pray tell me, who is the barbarian here, the murderer or the victim? I fling back in the teeth of those who make it this most false and foul aspersion upon the negro of the southern States.

—Robert Brown Elliott—

Elliott was reelected in 1872 and was very effective in his work in Congress, but he felt his party needed him more in his home state of South Carolina. He resigned his congressional seat in early November, 1784. He subsequently won a seat in South Carolina’s general assembly and was elected Speaker of the House. He was the second black to serve as Speaker in that body. He died on August 9, 1884.

It is very significant that all of these men, and more like them to follow, were Republicans.

This page is a part of a larger article.

Copyright © 2016 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All Rights Reserved.