The first recorded epidemic of polio in the United States occurred in 1894 in Rutland County, Vermont. From that point forward, for sixty years, the highly contagious disease threatened and victimized the people of the United States, especially children. Individuals

born before 1955 remember having a great fear of this horrible disease which crippled thousands of once active, healthy children. This disease had no cure and no identified causes, which made it all the more terrifying. People did everything that they had done in the past to prevent the spread of disease, such as quarantining areas, but these tactics never seemed to work. Polio could not be contained. Many people did not have the money to care for a family member with polio. This was one of the reasons the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis was organized. The March of Dimes, the fund raiser headed by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, raised thousands and thousands of dollars to help people care for their polio stricken family members and to aid in the cost of research for a vaccine that would put an end to this misery that affected the lives of so many people.

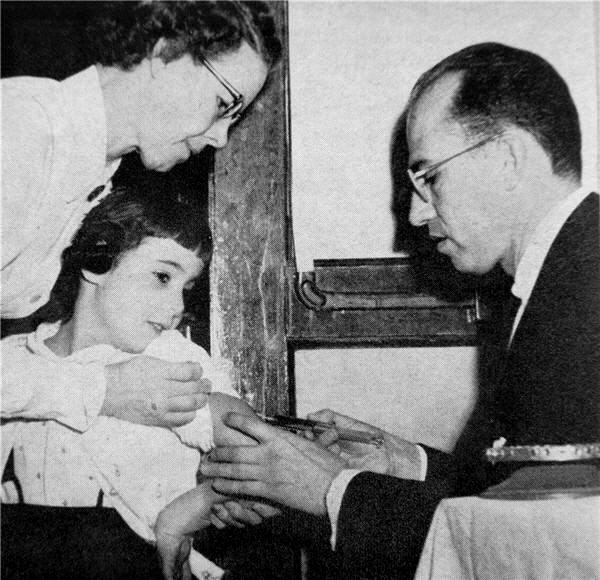

A breakthrough in the fight against the disease came on March 26, 1953 when, over nationwide radio, Dr. Jonas Salk announced that the initial tests he’d conducted on a vaccine had been successful. Researchers tested the vaccine widely in 1954, and doctors began inoculating patients routinely a year later. The results were remarkable. The number of cases of polio nationwide plummeted from 28,985 in 1955 to 5,894 two years later.

Nothing this significant could have taken place instantaneously. Dr. Salk began his research in 1947. During the next 8 years,

he spent tens of millions on his trials and eventually, starting in 1954, used over one million children in testing the vaccine. The March of Dimes contributed substantially to Salk’s work, which constituted the most extensive clinical trial in medical history. His colleagues were amazed by the number of hours Salk worked each day, including weekends, without letup.

Salk and his co-laborers did not pursue a patent for the vaccine. In an interview conducted by Edward R. Murrow, the researcher and physician famously said, “Could you patent the sun?”

It has been reported that a patent was researched but wasn’t pursued because lawyers believed it would not be granted (also go here). Even so, this doesn’t diminish the benefits that came to untold millions.

We should offer a couple of side notes.

- First, the trials weren’t completed without tragedy. One company manufactured its vaccines with a flawed process that resulted in 40,000 polio cases that critically paralyzed 200 children and took the lives of 10. When the flawed process was discovered, corrective measures were implemented, but of course no one could reverse the tragedies had occurred.

- Second, while the Salk vaccine relies on an inactivated or dead polio virus for its effectiveness, in 1961, a vaccine that relies on a weakened virus became available and overtook Salk’s. Administered orally, this immunization was developed primarily by Polish American medical scientist Dr. Albert Sabin. While history.com reports that the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that polio-free countries return to using the Salk vaccine, some health professionals have encouraged caution. Read the case for shifting back Salk’s approach here, and the warnings about making the change here. Don’t, however, miss the big picture. Without question, the work of both doctors have benefitted untold millions worldwide.

Why were Dr. Salk and his team successful? They respected reality and adjusted their work to absolute truth, to what was occurring in the real world.

This page is part of a larger article.

Copyright © 2017 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All rights reserved.