Uncomfortable Because People Prefer to Believe Lies Over the Truth; and Necessary Because Lies Are Dangerous, but the Truth Can Pull People and Society to Safety

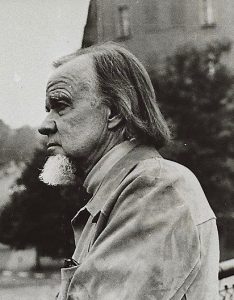

Francis Schaeffer (1912-1984) issued a warning through his writings that echoes down through the decades to the present day. The following quotations are from two of Schaeffer’s books — The Great Evangelical Disaster (1984) and How Should We Then Live? (1976)

Rightly defined, secular humanism — or humanism, or secularism, or whatever name you may wish to use — is…a vicious enemy. Here again balance is important by means of careful definition. The word humanism is not to be confused with humanitarianism, nor with the word humanities. But humanism is the defiant denial of the God who is there, with Man defiantly set up in the place of God as the measure of all things. For if the final reality is only material or energy which has existed forever and has its present form only by chance, then there is no one but finite man to set purely relative values and a purely relativistic base for law and government.1

[H]umanism haș no final way of saying certain things are right and other things are wrong. For a humanist, the final thing which exists — that is, the impersonal universe — is neutral and silent about right and wrong, cruelty and non-cruelty. Humanism has no way to provide absolutes. Thus, as a consistent result of humanism’s position, humanism in private morals and political life is left with that which is arbitrary.2

[H]umanism haș no final way of saying certain things are right and other things are wrong. For a humanist, the final thing which exists — that is, the impersonal universe — is neutral and silent about right and wrong, cruelty and non-cruelty. Humanism has no way to provide absolutes. Thus, as a consistent result of humanism’s position, humanism in private morals and political life is left with that which is arbitrary.2

If there is no absolute moral standard, then one cannot say in a final sense that anything is right or wrong. By absolute we mean that which always applies, that which provides a final or ultimate standard. There must be an absolute if there are to be real values. If there is no absolute beyond man’s ideas, then there is no final appeal to judge between individuals and groups whose moral judgments conflict. We are merely left with conflicting opinions.

But it is not only that we need absolutes in morals and values; we need absolutes if our existence is to have meaning — my existence once, your existence, Man’s existence. Even more profoundly, we must have absolutes if we are to have a solid epistemology (a theory of knowing — how we know, or how we know we know). How can we be sure that what we think we know of the world outside ourselves really corresponds to what is there? And in all these layers, each more profound than the other, unless there is an absolute these things are lost to us: morals, values, the meaning of existence (including the meaning of man), and a basis for knowing.3

Here is a simple but profound rule: If there are no absolutes by which to judge society, then society is absolute. Society is left with one man or an elite filling the vacuum left by the loss of the Christian consensus which originally gave us form and freedom in northern Europe and in the West. In communism, the elite has won its way, and rule is based upon arbitrary absolutes handed down by that elite. Absolutes can be this today and that tomorrow.…Arbitrary absolutes can be handed down and there is no absolute by which to judge them.4

[However, Christians recognize a set of absolute standards, so they have a “measuring stick” by which to evaluate the ideas that are “out there.” ] The “little man,” the private citizen, can at any time stand up and, on the basis of biblical teaching, say that the majority [or the elite] is wrong.5

The danger in regard to the rise of authoritarian government is that Christians will be still as long as their own religious activities, evangelism, and life-styles are not disturbed.

We are not excused from speaking, just because the culture and society no longer rest as much as they once did on Christian thinking. Moreover, Christians do not need to be in the majority in order to influence society.

But we must be realistic. John the Baptist raised his voice, on the basis of the biblical absolutes, against the personification of power in the person of Herod, and it cost him his head. In the Roman Empire the Christians refused to worship Caesar along with Christ, and this was seen by those in power as disrupting the unity of the Empire; for many this was costly.

But let us be realistic in another way, too. If we as Christians do not speak out as authoritarian governments grow from within or come from outside, eventually we or our children will be the enemy of society and the state. No truly authoritarian government can tolerate those who have a real absolute by which to judge its arbitrary absolutes and who speak out and act upon that absolute. This was the issue with the early church in regard to the Roman Empire, and though the specific issue will in all probability take a different form than Caesar-worship, the basic issue of having an absolute by which to judge the state and society will be the same.

Here is a sentence to memorize: To make no decision in regard to the growth of authoritarian government is already a decision for it.6

Notes:

1Francis Schaeffer, The Great Evangelical Disaster (Westchester, IL: Crossway Books, 1984), 105.

2Francis Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live? The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture, (Old Tappan, NJ: Fleming H. Revell, 1976), 128.

3Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live? 145.

4Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live? 224.

5Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live? 110.

6Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live? 256-257.

This page is part of a larger Word Foundations article.

When a Society Has Rejected Absolutes, It Is Vulnerable to Tyranny