A spring will cease to flow if its source be dried up; a tree will wither if it roots be destroyed. In its main features the Declaration of Independence is a great spiritual document. It is a declaration not of material but of spiritual conceptions. Equality, liberty, popular sovereignty, the rights of man – these are not elements which we can see and touch. They are ideals. They have their source and their roots in the religious convictions. They belong to the unseen world. Unless the faith of the American people in these religious convictions is to endure, the principles of our Declaration will perish. We can not continue to enjoy the result if we neglect and abandon the cause.

—Calvin Coolidge, on July 5, 1926, in a speech commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and consequently the 150th birthday of the United States of America—

This article is part 2 of a 3-part series highlighting ten bedrock principles of liberty embedded in the Declaration of Independence.

Last time we reviewed the discussion, debate, and activity—parliamentary and otherwise—that led to the drafting and adoption of the Declaration of Independence to give birth to the United States of America. These watershed events took place in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the Second Continental Congress, during June and early July of 1776.

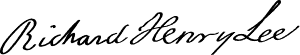

On June 7, Richard Henry Lee, a delegate from Virginia, presented a resolution to the Congress calling for the thirteen colonies to sever their ties to Great Britain. The first clause of the resolution read,

Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

Although Lee’s resolution was not voted on until July 2, when the Congress voted to approve it, a Declaration of Independence already had been drafted and refined by a drafting committee—a group that became known as the Committee of Five—and by the members of the Congress themselves. Thomas Jefferson, who later would become the third President of the United States, was the Declaration’s principal author….

To continue reading, go here.

Copyright © 2019 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All rights reserved.

top image credit: Liberty Bell Postage Stamp, 1926 — to learn more about the Liberty Bell, go here.

Be First to Comment