The Nile River isn’t just Egypt’s main river—it’s Africa’s main river. Flowing for a distance of some 2,500 miles from the equator’s Victoria Lake, it is the one river that flows northward through the Sahara. One-fifth of the length of the river, or 500 miles, is located in Egypt, with Ashwan marking the beginning of this portion of the river.

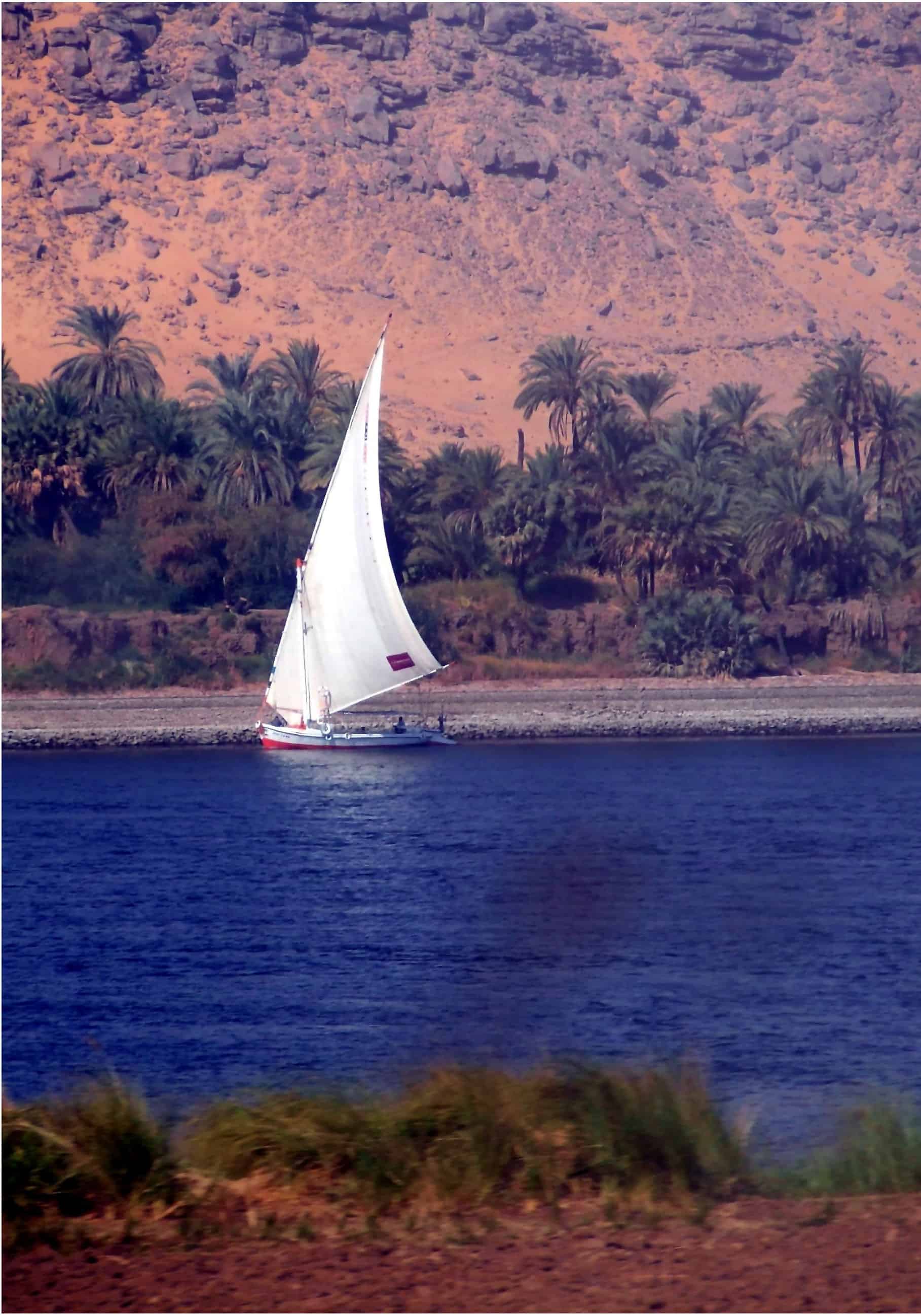

A felucca on the Nile near Aswan

The Nile River was the reason for the wealth of ancient Egypt; in fact, it was the source of its very life. Because of the Nile, Egypt was not dependent on rainfall, as other countries were, for survival. Each year, the runoff from Ethiopian rainfall during the winter caused the Nile to swell, and fertile silt was deposited in Egyptian land. This set the stage for the growing and harvesting of many crops, and of many kinds of crops, every year (see Ex. 16:3; Num. 11:5).

Famine resulted, however, if the winter rains did not occur in sufficient amounts. This could have been factor contributing to the 7-year famine that occurred during Joseph’s tenure as second-in-command in Egypt (see Gen. 41:54-56). Given this background, one can easily see how the first plague, in which the waters of the Nile were turned to blood (see Ex. 7:20-21,24-25), truly was devastating—and the plagues were just beginning! The second plague, a plague of frogs, involved the Nile as well (see 8:1-15).

The Nile River was the river that carried the infant Moses in a basket to a place where Pharaoh’s daughter saw it, investigated, and, in the end, adopted Moses (see Ex. 2:1-10). Ominously, it also was the river into which Pharaoh commanded infant Hebrew males like Moses be thrown (see 1:22). Isaiah 19:7 speaks of reeds growing by the Nile. Reeds had multiple uses. They could be eaten. They also provided material from which papyrus paper could be made. In addition, the stems of the plants could be used in making boats.

top image: The Finding of Moses, 1904, by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Copyright © 2017 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All rights reserved.