Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

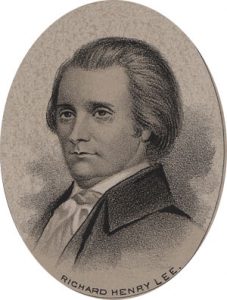

—Richard Henry Lee, in a motion made on June 7, 1776 during the Second Continental Congress—

Overview: The goal for this three-part series of articles is to mine from the most quoted portion of the Declaration of Independence what I’m calling bedrock principles of liberty. In parts 2 and 3 we will highlight and discuss ten such principles or truths. Some are obvious, but we have become too accustomed to the words and have grown increasingly unaware of their true meaning. In other cases, various ideals are implied rather than explicit, so one has to read between the lines. Because leftists often use the same words but with very different meanings, people frequently are duped by their emotional and passionate rhetoric. Going back to the Declaration of Independence and unearthing the intent of the Founders is an important step in effectively refuting the claims of the left and upholding the torch of authentic freedom. Here, in part 1, we will examine some historical events that led up to the adoption of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia during the first few days of July, 1776.

Talk among the American Colonists about the possibility and even the need to break ties with England had been occurring for some time, but not all the Colonists agreed that ties with the mother country should be severed, or that the time for a formal departure actually had arrived. It was against this backdrop that Richard Henry Lee of Virginia offered a clear and decisive resolution on Friday, June 7, 1776, during the Second Continental Congress. The motion readily was seconded by John Adams. It contained three clauses:

Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.

Members of the Congress tabled Lee’s motion until the following day. After discussion on the measure began and continued over a period of several days, it was determined that Lee’s motion would not be voted on until until July 1. Some delegates felt a break from the mother country might, at that point, be premature; so this move afforded them more time to think through the issue and its implications. It was June 10 when Edward Rutledge of South Carolina moved that the vote be delayed until the first day of July.1

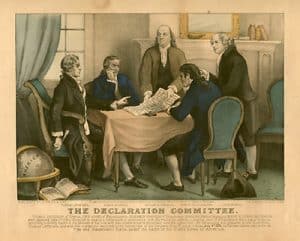

A Committee Appointed; A Draft Forged

Despite having agreed to postpone the vote on Lee’s motion, those assembled realized Congress was moving in the direction of adopting it. The delegates therefore deemed it prudent to form a committee to write a statement proclaiming independence—a rough draft for a declaration. They did so on Tuesday, June 11. The following five men were selected:2

-

-

- John Adams, 40, of Massachusetts,

- Roger Sherman, 55, of Connecticut;

- Robert Livingston, 29, of New York;

- Thomas Jefferson, 33, of Virginia; and

- Benjamin Franklin, 70, of Pennsylvania.

-

We see these men, who became known as the “Committee of Five,” depicted, left to right, in the center of artist John Trumbull’s well known work Declaration of Independence (shown at top). Trumbull (1756-1843) became known as “The Painter of the Revolution.”

How did the committee determine that Thomas Jefferson would write the draft? Writer and historian Stephen Puleo explains,

The Committee of Five met several times to consider the content of the document, and no one other than Adams and Jefferson was considered as a potential author; Benjamin Franklin was battling a severe attack of gout, and neither Roger Sherman nor Robert Livingston were considered especially gifted writers or lofty thinkers.…

An aging Adams [later] recalled that Jefferson urged him to write the Declaration draft, but Adams declined. When Jefferson asked why, Adams responded: “Reason first, you are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the end of this business. Reason second, I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. You are very much otherwise.” Was there a third reason? Yes, Adams said to Thomas Jefferson: “You can write ten times better than I can.” According to Adams, Jefferson replied: “Well, if you are decided, I will do as well as I can.”3

The above paragraph apparently is a summary of Adams’s recollections. In volume 1 of his three-volume overview of American history, America, The Last Best Hope: From an Age of Discovery to a World at War, 1492-1914, William J. Bennett cites Adams’s own words explaining why he wanted Jefferson to write the draft:

1. That [Jefferson] was a Virginian and I a Massachusettensian. 2. That he was a southern Man and I a northern one. 3. That I had become so obnoxious for my early and constant Zeal in promoting [Independence] that any [draft] of mine would undergo more severe Scrutiny and Criticism in Congress than one of his composition. 4thly and lastly that would be reason enough if there were no other, I had a great Opinion of the Elegance of his pen and none at all of my own.…He accordingly took and the Minutes and in a day or two produced to me his [draft].4

Jefferson’s recollections contrast sharply to those of his friend, John Adams. Stephen Puleo continues,

Jefferson’s account, [also] well after the fact, maintains that Adams’s advanced age (Adams was eighty-seven when he recounted the story, while Jefferson was eighty) had dulled his memory and led him “into unquestionabl[e] error.” He recalled no such exchange with Adams, remembering only that the committee met and “unanimously pressed” him to write the draft. “I consented; I drew it [up].”5

Independence Declared

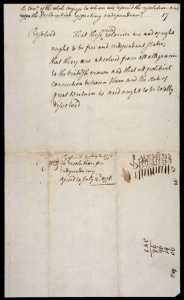

Lee’s resolution actually wasn’t voted on until July 2. The vote occurred after the delegates to the Second Continental Congress had received Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration from the committee and revised it in several places. The vote 1) made each colony a separate state, 2) called for establishment of alliances with other nations, and 3) established and proclaimed that the states now were free—independent of Great Britain. Here is a photo of a memo carrying the first clause of the Lee resolution.

In the lower right portion of this memo, we see a record of how each delegation voted. Of those who voted, all 12 were in agreement; New York abstained.

Thus, when the delegates were voting on Richard Henry Lee’s resolution, they also had a Declaration before them. The drafting committee already had made a few changes to Jefferson’s original wording; now the Congress itself made their refinements, discussing and debating the details. Deliberation “in Congress resulted in some alterations and deletions, but the basic document remained Jefferson’s. The process of revision continued through all of July 3 and into the late morning of July 4. [At last, t]he Declaration had been officially adopted.” Numerous attempts to capture the drama of the vote have been presented on radio. Go here to hear three.

The Pennsylvania Evening Post, a Philadelphia newspaper published by Benjamin Towne, was the first to release the news of the adoption of the Lee Resolution (the Post did so on the evening of July 2) and the second (also go here) to print the full text of the Declaration of Independence itself (on July 6).

Bedrock Principles

In parts 2 and 3 of this series, I would like to cite and uphold, from the most quoted statements of the Declaration of Independence, ten bedrock principles that are inherent in the document. They are not hidden, but in most cases they are assumed, and therefore evident by implication. These principles will demonstrate just how far America has departed from the foundational truths on which it was founded. Hopefully they also will serve as a warning to 21st-century Americans to rediscover these tenets, return to them, and embrace them once again.

I plan to release part 2 on Monday, July 8. Stay tuned!

Part 2 is available here.

Copyright © 2019 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All rights reserved.

Notes:

1Stephen Puleo, American Treasures (pp. 34-35). St. Martin’s Press. Kindle Edition.

2Puleo, 35-36.

3Puleo, 36-37.

4William J. Bennett, America: the Last Best Hope, Volume 1: From the Age of Discovery to a World at War, 1492-1914, (Nashville: Thomas Nelson / Nelson Current, 2006), 83.

5Puleo, 37.

[…] To continue reading, go here. […]

[…] series mining ten bedrock principles of liberty embedded in the Declaration of Independence. In part 1 we reviewed some of the events that led to the adoption of the Declaration of Independence in early […]