What are liberty’s essential underpinnings? Despite their flaws, America’s Founders knew, and they risked their lives to uphold them.

The Declaration of Independence laid the cornerstone of human government upon the first precepts of Christianity.

—John Adams—

Key points: With Independence Day just over six weeks away, now is a great time to learn about the biblical underpinnings of the principles of liberty we find embedded in the Declaration of Independence. You’re invited to explore these in this article and in this Bible study series; but first, I’d like you to meet a very courageous woman who proved just how important America’s founding principles really were, and are.

The true story of Elizabeth Freeman is one of many remarkable stories to come out of the American Revolution. This courageous lady wasn’t always known as Elizabeth Freeman; earlier in life she was known as Bett. She was born into slavery in or around 1742 in Claverack, a town in eastern New York. At the time, slavery was legal in all of the thirteen colonies.

The farm on which Bett was born belonged to a man named Pieter Hogeboom. When Bett was seven years old, Hogeboom’s daughter, Hannah, married John Ashley, a resident of Sheffield, a town in western Massachusetts. Hogeboom gave Bett and possibly her sister to Hannah and her new husband, so Bett (with or without her sister) moved Massachusetts and began serving the Ashleys. John Ashley was a wealthy and influential landowner and a prominent member of the local community, as well as of the state.

Bett’s life was difficult under the Ashleys. Some researchers believe that by 1780, Bett had a young daughter who also was their slave (or the following incident may have involved Bett’s sister; there is disagreement on this point). On one particular occasion during that year, “Mrs. Ashley attacked Freeman’s young daughter [or sister] with a heated shovel,…[and Bett] blocked the blows with her own body, leaving a deep wound.” The resulting scar on Bett’s arm would become to the courageous woman “a badge of her family’s mistreatment”; she consistently resisted concealing it.

As a judge in the local area, John Ashley helped draft what become known as the Sheffield Declaration, or the Sheffield Resolves. This “petition against British tyranny and manifesto for individual rights” was adopted on January 12, 1773. The Declaration

stated that “mankind in a state of nature are equal, free, and independent of each other, and have a right to the undisturbed enjoyment of their lives, their liberty and property.” [As we will note in a moment, t]his same language was used in the United States Declaration of Independence of 1776 and in the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780.

RESOLVED, That mankind in a state of nature are equal, free, and independent of each other, and have a right to the undisturbed enjoyment of their lives, their liberty and property.

—The Sheffield Declaration, 1773—

Did Bett overhear discussions about the document and the noble ideal it would uphold when it was completed? Apparently she did! Later, did she readily understand that the newly adopted Massachusetts Constitution upheld the same principle with the words “all men are born free and equal”? Yes, and she also realized that she could not reasonably be counted an exception; she knew that as a member of “mankind” she, too, was “born free and equal.”

The principal writer of the Sheffield Declaration was Theodore Sedgwick, also a prominent and influential citizen of Sheffield. During his lifetime, Sedgwick became acquainted with many noteworthy American leaders of that era, including George Washington, John Jay, and Alexander Hamilton. Bett went to him and asked him to help her sue for her freedom in court, under the new Massachusetts Constitution.

Mr. Sedgwick did indeed assist Bett, but he felt he would have a much better chance of winning her case if a man also became a plaintiff with her. Another slave owned by the Ashleys, Brom, joined in the suit, and in 1781 Sedgwick, assisted by legal scholar Tapping Reeve,

challenged their enslavement under the new state constitution of 1780, which [as we have stated,] held that “all men are born free and equal.” The jury agreed and ruled that Bett and Brom were free. The decision was upheld on appeal by the state Supreme Court.

In an article appearing at historynet.com, J.D. Zahniser summarizes the case and its aftermath:

In August 1781, at Great Barrington, Massachusetts, the Berkshire County Court of Common Pleas heard the case of Brom and Bett v. Ashley. Addressing a jury of free White men, Sedgwick and Reeve argued that the language of the new state constitution effectively outlawed slavery. Though in 1781 these veniremen were hardly a jury of the plaintiffs’ peers, few jurors hearing the case were likely to own slaves. By the next day, the jury had found for Bett and Brom: the two were free people. Bett and Brom were awarded 30 shillings in damages. [John] Ashley was ordered to pay six pounds in court costs. Ashley appealed but within months, after a similar suit was also decided in favor of the enslaved, dropped his appeal.

Another such case brought about the legal end of slavery in Massachusetts when on July 8, 1783, the state supreme court ruled in Commonwealth v. Jennison. In that finding the judge referenced the new state constitution’s declaration that “all men are born free and equal” in stating that “slavery is in my judgment as effectively abolished as it can be….”

…Bett took the name Elizabeth Freeman and began to fashion a free life. [Later, she would come to be known as “Mumbet.”] John Ashley offered her a paid position, but she went to work for Theodore Sedgwick. Freeman acquired a reputation as a midwife and nurse.

Elizabeth Freeman became one of the first female property owners in Massachusetts, writes podcaster Yves Jeffcoat. Her case and others like it “marked the beginning of the end of slavery in Massachusetts.” And with an end to slavery, former slaves began to taste the freedom and opportunities that go with liberty.

Yes, the new nation still had a very long way to go in honoring the ideal that “all men are born free and equal.” Moreover, liberty’s opportunities for former slaves, when they did come, often came slowly and haltingly. Yet, as Elizabeth Freeman’s story proves, these blessings begin to arrive for some even in the early years of the United States of America.

This 7-minute video is titled “The Legacy of Elizabeth Freeman: A Story of Justice and Freedom.” Watch and listen as Mark Wilson of the Trustees of Reservations in Massachusetts tells Elizabeth’s inspiring story. A shorter video is available here.

Courageous People; An Unshakeable Ideal

While it certainly is right and proper to celebrate courageous women and men like Elizabeth Freeman, Brom, Theodore Sedgwick, and others; we must not overlook the thoroughly biblical ideal on which they based their courageous actions. Moreover, if we truly are fair-minded, we also cannot overlook, nor can we malign, the men who upheld the bedrock truth expressed in the Massachusetts Constitution as “all men are born free and equal” and in the Declaration of Independence as “all men are created equal,…[and] are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

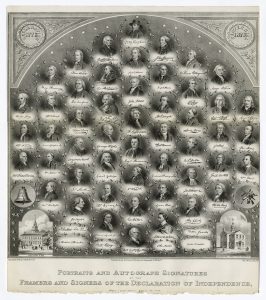

Today, a great deal of criticism is leveled against the architects and signers of the Declaration of Independence of 1776 and the US Constitution, drafted in 1787, because these men spoke of and wrote about equality, yet allowed slavery to remain legal, at least for the time being, in the new nation.

It’s true that some were slaveholders. Yet, like Elizabeth Freeman, they also were born into and “grew up in a world where slavery was legal in essentially every state, nation, and empire.” Can we not remember that despite the harsh reality that slavery was woven into the cultural fabric of that day, 56 men put their lives on the line when they signed the Declaration of Independence, a document that upheld the ideal that all men — all people — are created equal and that governments are established protect and maintain God-given rights?

The negative posture the Constitution of 1787 took toward slavery is familiar to very few today, but the Constitution for the new nation still placed it on a track that eventually would lead to slavery’s end. Sadly, the institution’s demise would come decades later and after a bloody Civil War, but it would come nonetheless.

Was the problem the Constitution as it originally had been drafted? Not according to slave-turned-abolitionist-and-patriot Frederick Douglass. In 1852 he said, “Now, take the Constitution according to its plain reading, and I defy the presentation of a single pro-slavery clause in it. On the other hand it will be found to contain principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.” Once he reached his pro-Constitution convictions, Douglass never wavered. The battle for civil rights for blacks would continue well into the 20th century, but in 1893 Douglass declared, “There is no Negro problem… The problem is whether the American people have honesty enough, loyalty enough, honor enough, patriotism enough, to live up to their own Constitution.”

Now, take the Constitution according to its plain reading, and I defy the presentation of a single pro-slavery clause in it. On the other hand it will be found to contain principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.

—Frederick Douglass—

An honest and fair assessment of history informs us that the concept that “all men are created equal” became one of the most powerful ever upheld by a nation. As historian William Bennett writes,

the Founders did not immediately free the slaves, give votes to their wives, or invite the Indian tribes to sign the Declaration with them…all of the greatest advocates for human equality in America—Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Suffragettes, Martin Luther King Jr.—pointed to this passage in the Declaration to give force to their demands for justice.1

Not Just One Unshakeable Ideal, But Many

Frederick Douglass had tremendous praise for the the Founders of the United States of America. Although in this quote he mentions the Framers of the Constitution, his description also applies to the architects and signers of the Declaration of Independence, which had been adopted eleven years earlier. Douglass said,

The Constitutional framers were peace men; but they preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage. They were quiet men; but they did not shrink from agitating against oppression. They showed forbearance; but that they knew its limits. They believed in order; but not in the order of tyranny. With them, nothing was “settled” that was not right. With them, justice, liberty and humanity were “final;” not slavery and oppression.

This, I believe, is an apt description of America’s Founders. Why? They believed in the God of the Bible and upheld the principles it taught. Further, they did not hesitate to uphold their convictions in their deliberations on national and public affairs.

In 2019, I wrote a series of articles highlighting “Principles of Liberty,” ten ideals upheld in the Declaration of Independence. These ten principles — all of them — were and are thoroughly biblical, and they include several tenets that overlap the one that a Massachusetts court upheld in 1781 when it granted Elizabeth Freeman and her fellow slave Brum their freedom.

A year later, in 2020, I created and released a Bible study to help readers explore these principles, their biblical and theological underpinnings, and the historical context in which they were upheld by the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Although imperfect, the Founding Fathers of the United States of America understood what makes liberty possible. We need to learn about liberty from them today — but most importantly, we need to come to discover, or rediscover, the biblical principles they upheld in the Declaration.

The immediate need to understand the true nature of liberty is extremely great in our country. This is especially the case among followers of Christ, given the fact that liberty’s supports are thoroughly Christian.

The Bible study is designed for groups, but individuals can take advantage of it by exploring the material on their own. With Independence Day only a few weeks away, there is no better time than now to read about and study “Ten Biblical Truths Embedded in the Declaration of Independence.”

Just how important are these principles? If we could, we would ask Elizabeth Freeman. She’d tell us that to her, they made the difference between slavery and freedom, the difference between misery and her being able to chart her own “pursuit of happiness.”

Were we able to ask the same question of America’s Founders, I believe they’d also acknowledge the blessings of liberty, but they would speak of them not just for individuals, but for the nation. I wouldn’t be surprised to hear them say they came to understand that these tenets are so important they actually can make the difference between America’s slavery to false ideas, and true freedom.

So must we.

Copyright © 2022 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All rights reserved.

A printable list of the ten biblical principles embedded in the Declaration of Independence is available here.

top image credit: Photo by Thomas Bormans on Unsplash

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture has been taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Note:

1William J. Bennett, America, the Last Best Hope—Volume 1: From the Age of Discovery to a World at War, (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2006), 86.

Be First to Comment